The Spring by Franz Xaver Winterhalter

Every year, as the Spring Equinox arrives, a familiar debate reignites:

Is Ostara an ancient Pagan holiday? Was Ēostre worshiped, or was she an invention?

Detractors often claim that Ēostre, the supposed Anglo-Saxon spring goddess, is nothing more than a fabrication by the 8th-century monk Bede. In contrast, others dismiss Ostara as a 19th-century reconstruction by the Brothers Grimm. This year, everyone is talking about Aiden Kelly and Wicca. While a few years ago it was en vogue to try to connect Easter to the Mesopotamian goddess Ishtar, a linguistic mix-up with little historical backing.

But the evidence tells a far more compelling story.

Through linguistic studies, Indo-European mythology, archaeological discoveries, and even regional folk traditions, we find deep-rooted connections between Ostara, Ēostre, and the veneration of a Dawn Goddess who was honored across ancient Indo-European cultures.

Let’s set the record straight.

The real question isn’t whether Ostara “existed” in the way modern people demand proof. It’s about whether we allow the past to be more than what was written down.

We live in a time where certainty is worshipped. People want hard evidence, absolute facts, and things that fit neatly into academic categories. But pre-Christian traditions weren’t built that way.

Our ancestors didn’t write scholarly essays about their gods and festivals. They lived them. They saw them in the land, the sky, the turning of the seasons. Their gods weren’t fixed, universal figures. They were fluid, local, and deeply intertwined with the cycles of nature.

So if all we have are a few lines from Bede, a name passed down, or symbols that persist in folk traditions—what do we do with that?

We expand the conversation.

1. We look to the land. If rabbits, eggs, and the first warmth of the sun symbolize renewal today, why wouldn’t they have symbolized it then? We don’t need written permission to recognize what’s right in front of us.

2. We trace the patterns. The Indo-European dawn goddess archetype, the Matronae Austriahenae inscriptions, the echoes of seasonal rebirth myths across cultures—these all point to something older than Christianity. Something deeply woven into the human experience of spring.

3. We do the spiritual work. The Old Powers are not confined to history books. They don’t need footnotes to be real. They are felt in ritual, in intuition, in personal connection.

This is why the debunking mindset fails. It acts as if we are separate from history as if the past is a dead thing we can “prove” or “disprove” with a few citations. But history isn’t dead. It’s alive. It breathes in the folk traditions that survived, in the stories we retell, in the practices we revive.

The real mistake isn’t in believing Ostara was worshipped.

The real mistake is believing the past can be fully known at all.

Instead of asking, “Did she exist?” Maybe we should ask, “How do we honor her now?”

Let’s start unpacking it.

Ostara (1884) by Johannes Gehrts.

Bede, the Reckoning of Time & the Name Ēostre

The earliest written reference to Ēostre comes from Bede’s De Temporum Ratione (The Reckoning of Time, 725 CE). He states:

“Eosturmonath was once called after a goddess of theirs named Ēostre, in whose honor feasts were celebrated in that month. Now they designate that Paschal season by her name, calling the joys of the new festival by the time-honored name of the old observance.”

Skeptics argue that because Bede was a Christian monk, we should question the legitimacy of his claim. But there are several problems with dismissing Bede outright. First, Bede was known for his accuracy. He was a meticulous historian, and if he included a reference to an Anglo-Saxon goddess, he likely had sources to support it. Additionally, no other English month names are based on deities. The Anglo-Saxon calendar had months named for seasons and agricultural cycles. The presence of a deity-named month (Ēosturmōnaþ) suggests a real religious significance.

Another important factor is that Christian chroniclers rarely “invented” pagan gods. They recorded existing beliefs to discredit them—not to fabricate them. While we lack extensive writings on Ēostre, this is not surprising. Pagan traditions were primarily oral, and Christianity often erased or absorbed existing beliefs.

But Bede’s account is only one piece of the puzzle.

Aurora Taking Leave of Tithonus- j. Paul Getty

Jacob Grimm, Proto-Indo-European Roots & the Goddess of the Dawn

In the 19th century, Jacob Grimm, one of the famous Brothers Grimm, expanded on Bede’s account in his book Teutonic Mythology (1835). He proposed the existence of a Germanic goddess named Ôstarâ, linking her name to the Old High German Ostara and reconstructing the Proto-Germanic form Austra… which sounds a lot like Ēostre. Grimm didn’t make up stories, he made it his life’s work to collect local legends, myths, and folklore so they wouldn’t be lost. He studied linguistics to try to understand how it fit together.

This is where the linguistic trail leads us deeper. The name Ostara/Ēostre comes from Proto-Germanic austrōn, meaning “dawn.” This is connected to the Proto-Indo-European root h₂ews-, meaning “to shine” or “dawn.” Cognates exist across Indo-European languages, including Greek Eos (Goddess of the Dawn), Roman Aurora (Dawn), Vedic Hindu Uṣás (Goddess of the Dawn), and Baltic Aušrinė (Morning Star Goddess).

The Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture confirms that:

“A Proto-Indo-European goddess of the dawn is supported both by the evidence of cognate names and the similarity of mythic representation of the dawn goddess among various Indo-European groups.”

So it seems rather probable that the Anglo-Saxons had their own goddess of the dawn.

Grimm’s reconstruction was ahead of his time. Decades later, archaeological discoveries would further support his theory.

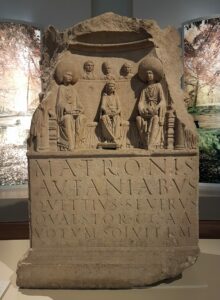

The Matronae Austriahenae

The Matronae Austriahenae: Archaeological Evidence of a Dawn Goddess

In 1958, over 150 votive inscriptions dedicated to the Matronae Austriahenae were discovered near Bonn, Germany.These date to the 2nd century CE. The Matronae (or “Mothers”) were Germanic goddesses honored in the Rhineland region under Roman rule. They were depicted as three women, one younger and two older, often holding symbols of fertility.

The name Austriahenae closely resembles Austra—Grimm’s reconstructed Proto-Germanic dawn goddess. This discovery provides physical evidence of a divine feminine figure connected to dawn, fertility, and renewal. Scholars now widely accept that the Matronae Austriahenae may be the historical precursors to Ēostre/Ostara.

Before this find, skeptics dismissed Grimm’s theory, claiming there was no evidence beyond Bede’s mention. Now, we see that a dawn goddess was indeed worshiped in Germanic lands.

Freya by Roberto Campus

Why Didn’t Ēostre Survive?

Another common argument against Ēostre is: “If she was real, why isn’t she widely known in Germanic mythology?”

The answer is simple: Not every deity was worshiped everywhere.

Germanic traditions were highly regional. Local gods often didn’t make it into major written records. Many gods and goddesses faded as cultures shifted or Christianization took hold. Bede himself alludes to this when he mentions her. However, the dawn goddess might have left her mark in other ways, such as in the Valkyries (whose names often reference brightness) and figures like Freyja, associated with fertility and renewal. Ēostre’s absence in other written texts does not mean she didn’t exist. It simply means our records are incomplete.

The Easter Bunny, Eggs & Folk Traditions

Even if the goddess Ēostre was nearly forgotten, her symbols might remain. Eggs have been ancient symbols of fertility, renewal, and cosmic creation for eons. Hares and rabbits, sacred animals in fertility traditions, are possibly linked to the “Osterhase” (Easter Hare), a German folk tradition, but they are most certainly connected to spring and fertility.

The “Cosmic Egg” myth, found in Indo-European and other cultures, links the cracking of the egg to the birth of the world, which in many cultures was believed to happen in the Spring.

A rather modern (by history’s standards) Germanic folktale tells that the goddess Ostara found an injured bird and transformed it into a hare, which then laid eggs in gratitude. This legend speaks to our mythic minds, and how our ancestors saw that world. I’ve said it before, and I’ll say it again, stories and myths are the sacred texts of our ancestors. They are the closest things we have to understanding their worldview.

The Gates of Dawn, by Herbert James Draper

Final Thoughts: Why This Matters

The push to “debunk” Ēostre and Ostara is part of a larger trend of dismissing oral traditions and regional deities. But as we’ve seen, the linguistic, archaeological, and cultural evidence overwhelmingly supports the existence of a Germanic dawn goddess linked to broader Indo-European traditions.

This isn’t just about Ostara. It’s about how we approach all of our ancestral traditions.

🔹 Do we demand rigid proof before we allow something to be sacred?

🔹 Do we dismiss practices just because they weren’t documented in ways we’re comfortable with?

🔹 Or do we embrace curiosity, connection, and sacred reclamation—understanding that history is a living, evolving thing, and we are actually part of it?

This is something I return to again and again in my work—whether I’m exploring the ancient roots of Santa Claus, Valentine’s Day, Groundhog Day, or ancestral rituals and seasonal celebrations like Carnevale. The past isn’t gone. It’s just waiting for us to pay attention!

So, this spring, when someone asks if Ostara is “made up,” you can tell them:

The dawn goddess has always been with us.

She shines in the first light of morning, in the renewal of spring, and in the stories passed from our ancestors.

She was never lost—only waiting to be remembered.

List of Resources to Learn More:

For those interested in diving deeper into the history, linguistics, and cultural significance of Ostara, Ēostre, and the Dawn Goddess, please check out my March Seasonal Guide: Hope Spring Eternal and the Old Ways for Modern Days podcast episode: Ostara. In addition, here are some key academic and historical sources:

- Bede, De Temporum Ratione (The Reckoning of Time) – The 8th-century source that first mentions Ēostre.

- Jacob Grimm, Teutonic Mythology, Volume 1 (1835) – Explores Germanic and Indo-European dawn goddesses, reconstructing Ostara from linguistic evidence.

- Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture, Mallory & Adams (1997), pp. 148–149 – Discusses the widespread Proto-Indo-European dawn goddess across various cultures.

- Matronae Austriahenae inscriptions (1958 discovery, near Bonn, Germany) – Physical evidence of goddess worship in the Germanic regions with linguistic ties to Ostara.

- Kim Rendfeld, Yes, the Anglo-Saxon Spring Goddess Eostre Did Exist (2017) – Argues why Ēostre’s absence in Norse sources does not disprove her worship.

- Georg Franck von Franckenau, De ovis paschalibus (1682) – The earliest written reference to the Easter Hare (Osterhase).

- Smithsonian Magazine, The Ancient Origins of the Easter Bunny – Explores how pagan fertility symbols were absorbed into Christian traditions.

- History Cooperative, The Origin of Easter Eggs – Examines the cosmic egg motif in Indo-European and global traditions.

- Kvilhaug, Maria, Ēostre – Easter, Spring Celebrations and the Pagan Goddess https://bladehoner.wordpress.com/2022/04/12/eostre-easter-spring-celebrations-and-the-pagan-goddess/

(added April 15, 2025)

These sources provide historical, linguistic, and archaeological backing for those interested in further study. I will keep adding more articles, as I come across them.

My Articles Related to Spring and the Spring Equinox:

Spring Equinox: The Magic of the Cosmic Egg

Thresholds to the Otherworld: Thorn & Hedge Magic

Artichoke Magic: Spring in Sardinia

[/fusion_text][/fusion_builder_column][/fusion_builder_row][/fusion_builder_container]

Leave a Reply