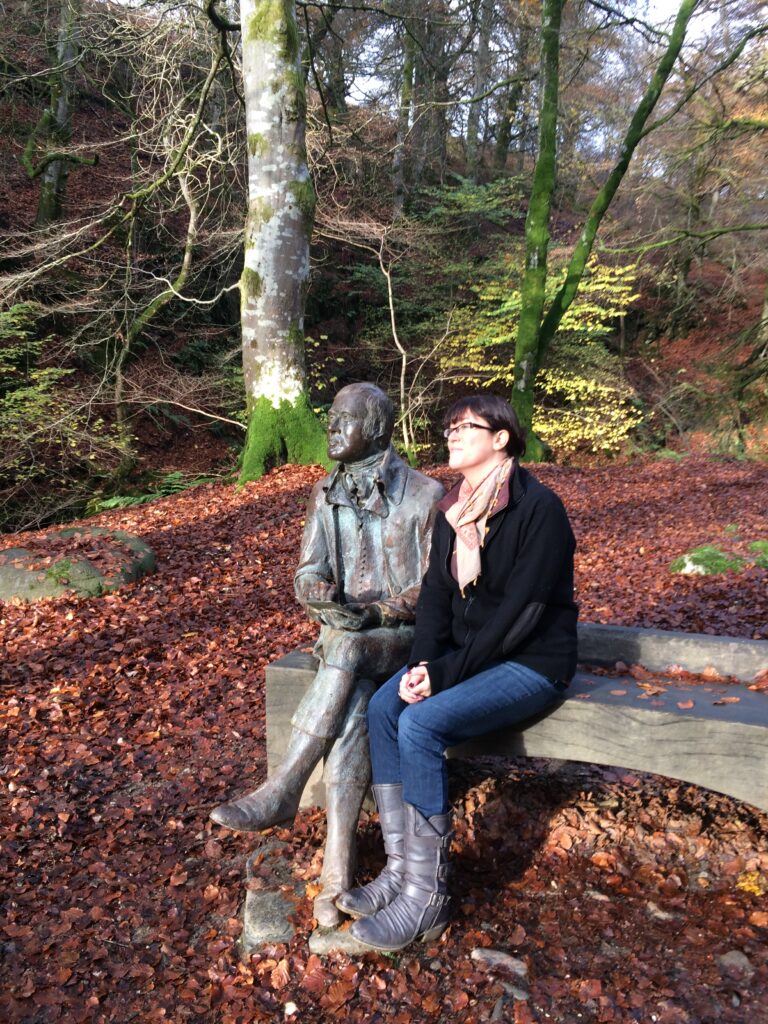

Me and Robert Burns at the Birks O’ Aberfeldy in 2014

Robert Burns, Scotland’s cultural ancestor, championed the common people, their struggles, and their stories. Learn about his revolutionary ideas, the importance of tradition (and how they can go together!), and how celebrating Burns Night keeps his legacy alive.

My heart’s in the Highlands, my heart is not here,

My heart’s in the Highlands, a-chasing the deer;

Chasing the wild-deer, and following the roe,

My heart’s in the Highlands, wherever I go.— Robert Burns, 1789

Burns Night, celebrated every January 25th, is a tribute to Scotland’s national bard. Yet, it is also a celebration of connection—connection to heritage, to the land, and to each other. For me, this night is deeply personal, which is why it is an important entry on my family’s ritual calendar, as it weaves together family stories, ancestral roots, and inspiration as a writer for the profound respect of the enduring power of words. I feel my connection to Robert Burns through all of these threads.

When I had the privilege to meet my birth family years ago, one family member who is very knowledgeable about family history told me a family story. It was about one of my great-grandfathers, a naturalist from Ayrshire, who is said to have known Robert Burns. According to the tale, they worked the same fields, walking the rolling hills that so often inspired Burns’ poetry. Whether this story is true or simply part of the mythology of my family, it feels like a thread connecting me to both my bloodline and the wider cultural tapestry of Scotland.

Every Burns Night, as I recite his poems like a prayer, I am reminded of this connection—not just to my family, but to the land itself and the people who call it home.

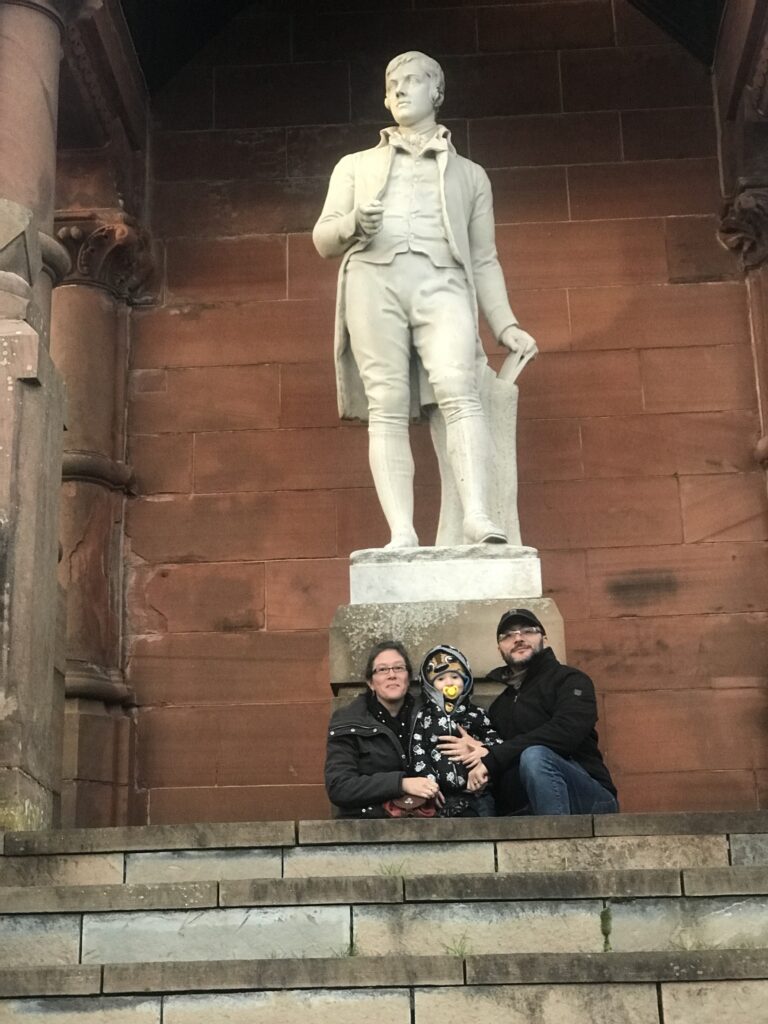

Me and My Roberts: Burns Monument in Kay Park in the town of Kilmarnock, where generations of my ancestors lived. My son is also the 4th Robert in his lineage.

Robert Burns: A Voice of the Land & Its People

Robert Burns is celebrated for many reasons: his wit, his romanticism, and his fierce intellect. But what has always struck me most is his ability to give voice to the land and its people. Burns wrote in Scots, the language of the common folk, at a time when it was often dismissed as crude or unworthy of art. By elevating Scots, he preserved a linguistic heritage that might otherwise have been lost, much like the landscapes he so lovingly described in his work.

What I love about the Scots language is that it is accessible to English speakers. We may not understand everything, but we can often get the gist. The Scottish government officially recognizes the language as an indigenous language of Scotland, as well as a minority language of Europe and a vulnerable language by UNESCO.

Burns knew how important it was to make art accessible for all. In fact, his poetry is deeply rooted in the struggles of the common man and often points to humankind’s need to be in the right relationship with the land while speaking to the struggles of tenant farmers.

In To a Mouse, Burns captures this belief by saying: I’m truly sorry man’s dominion,

Has broken nature’s social union,

An’ justifies that ill opinion,

Which makes thee startle

At me, thy poor earthborn companion,

An’ fellow-mortal!

While in A Man’s a Man for A’ That, he envisions a world where equality triumphs over class distinctions.

A prince can mak a belted knight,

A marquise, duke, an’ a’ that;

But an honest man’s aboon his might,

Gude faith, he maunna fa’ that!

For a’ that, an’ a’ that,

Their dignities an’ a’ that,

The pith o’ sense, an’ pride o’ worth,

Are higher rank than a’ that.

He also was outspoken about Independence for Scotland. From Scots Wha Hae:

By Oppression’s woes and pains,

By your sons in servile chains!

We will drain our dearest veins,

But they shall be free.

Lay the proud usurpers low,

Tyrants fa in every foe,

Libertie’s in every blow!—

Let us do or dee.

Burns understood the grief of losing traditional ways of life, lamenting the encroachment of industrialization and the displacement it brought to rural communities. So he traveled around Scotland recording traditional songs so they wouldn’t be forgotten.

Yet, even as he mourned what was being lost, Burns celebrated the enduring beauty of the natural world. Like the wild deer he wrote about, his words roam freely through time, reminding us of the bond between the land and those who live upon it.

Robert Burns’ legacy is a powerful reminder that revolutionary ideas and tradition are not mutually exclusive. While his poetry and songs challenged social norms and championed equality, he also dedicated himself to preserving Scotland’s cultural heritage by collecting and revitalizing traditional folk songs and writing his works in Scots, ensuring that the voices of the past continued to resonate with future generations.

Cultural Ancestors & the Legacy of Storytelling

While Burns was not a blood ancestor, I think of him as a “cultural ancestor.” He is part of the lineage of storytellers, poets, and dreamers who have shaped my own identity as a writer. Burns reminds us that our ancestors are not only those connected to us by DNA; they are also the voices who speak to our hearts, who inspire us to think deeply, and who challenge us to see beauty in struggle.

Like Burns, I’m often longing for a different way of life and processing that grief and melancholy through writing and sharing stories that I hope inspire other Old Souls in some way to continue to find beauty in our modern lives.

My family story about Burns is, in many ways, more important than its factual accuracy. As a dear friend, Dr. Gina Miele, a professor of folklore, once told me, it’s through stories that we recognize and know each other. She says that we have to tell our family stories, especially those we’ll never be able to verify. These stories create a bridge to our Ancestors, a common mythology with which we can recognize each other. So, Whether true or not, my family story bridges the past and present, linking me to the Bard of Ayrshire in a way that feels deeply meaningful.

My Daughter, Alba enjoying haggis 2015

Haggis & the Spirit of Celebration

Central to Burns Night is the haggis, that humble yet iconic dish immortalized in his Address to a Haggis:

Fair fa’ your honest, sonsie face,

Great chieftain o’ the puddin’-race!

Haggis, made from sheep’s offal, oats, and spices, is a celebration of resourcefulness and community. For Scots, it embodies a connection to the land and the ingenuity of those who made the most of what they had.

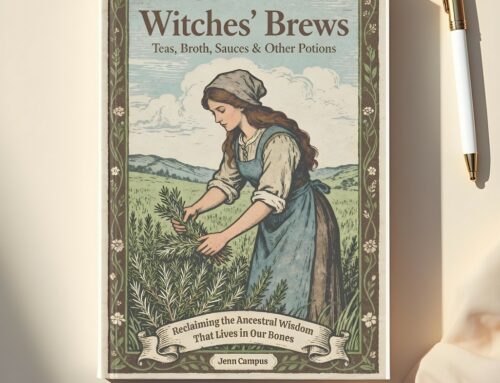

But what if haggis is unavailable or unwelcome at your table? Burns Night is ultimately about the spirit of connection, not just the menu. Instead of haggis, consider hearty Scottish dishes like Scotch Broth, Cullen Skink, or oatcakes with local cheeses and chutney. You could even create a vegetarian haggis, combining lentils, barley, mushrooms, and warming spices.

Homemade oatcakes& cheeses

Celebrating the Bard, Near & Far

For me, celebrating Burns Night isn’t just about what’s on the table—it’s about what’s in our hearts. Living in Sardinia, I can’t recreate the grand Burns Suppers of my Vermont homestead, where friends gathered to share haggis, neeps (I can’t even get them in Sardinia! But now that we have our own land, I will start growing them), and tatties while a harpist played traditional Scottish tunes. Instead, I’ve adapted the celebration to my current home with a hearty Scotch Broth and my famous oatcakes with smoked salmon, cheese, and chutney– and focus on the words of the bard himself.

Each year, I recite Burns’ poetry, listen to music inspired by his work, and raise a glass of whisky to his memory. And each year, I feel the presence of my Ayrshire roots and the enduring beauty of Scotland’s cultural heritage.

Ayrshire Coast

Why Burns Night Matters

Burns Night is a chance to reflect on what it means to be part of a lineage—not just of family, but of culture and tradition. It’s a time to honor the storytellers and poets who remind us of our shared humanity and the beauty of the world around us.

Whether you celebrate with haggis or Scotch Broth, whisky, or tea, the heart of Burns Night lies in connection to our ancestors, to the land, and to each other.

So, on January 25th, as I light a candle and recite My Heart’s in the Highlands, I’ll raise a toast to Robert Burns and to all those who came before us, whose words and actions continue to guide us.

Cheers, Slàinte Mhath, and Happy Burns Night!

Related Posts:

Celebrating Scottish American Heritage Month: A Guide to Ancestral Connection

Leave a Reply